What Size Thyroid Nodule Should Be Removed

- Review article

- Open Admission

- Published:

Thyroid nodule update on diagnosis and management

Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology volume two, Article number:17 (2016) Cite this article

Abstruse

Thyroid nodules are common. The clinical importance of thyroid nodules is related to excluding malignancy (4.0 to 6.5% of all thyroid nodules), evaluate their functional condition and appraise for the presence of pressure level symptoms. Incidental thyroid nodules are being diagnosed with increasing frequency in the recent years with the use of newer and highly sensitive imaging techniques. The high prevalence of thyroid nodules necessitates that the clinicians use evidence-based approaches for their assessment and management. New molecular tests accept been developed to assist with evaluation of malignancy in thyroid nodules. This review addresses advances in thyroid nodule evaluation, and their direction because the current guidelines and supporting evidence.

Background

Thyroid nodule is a discrete lesion in the thyroid gland that is radiologically singled-out from the surrounding thyroid parenchyma [1]. Thyroid nodules are mutual; their prevalence in the general population is high, the percentages vary depending on the way of discovery: ii–half dozen % (palpation), 19–35 % (ultrasound) and 8–65 % (autopsy data) [2–4]. They are discovered either clinically on cocky-palpation by a patient, or during a physical examination by the clinician or incidentally during a radiologic procedure such as ultrasonography (US) imaging, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck, or fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography; with the increased apply of sensitive imaging techniques, thyroid nodules are being diagnosed incidentally with increasing frequency in the contempo years [5, 6]. Though thyroid nodules are common, their clinical significance is mainly related to excluding malignancy (4.0 to six.5% of all thyroid nodules) [3, vii–9], evaluating their functional status and if they crusade pressure level symptoms.

Diagnosis and evaluation of thyroid nodules

Thyroid nodules can be caused past many disorders: beneficial (colloid nodule, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, simple or hemorrhagic cyst, follicular adenoma and subacute thyroiditis) and malignant (Papillary Cancer, Follicular Cancer, Hurthle Cell (oncocytic) Cancer, Anaplastic Cancer, Medullary Cancer, Thyroid Lymphoma and metastases −3 most common primaries are renal, lung & head-neck) [3, 10, 11].

Initial assessment of a patient found to have a thyroid nodule either clinically or incidentally should include a detailed and relevant history plus physical exam. Laboratory tests should begin with measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Thyroid scintigraphy/radionuclide thyroid scan should be performed in patients presenting with a low serum TSH [one]. Thyroid ultrasound should be performed in all those suspected or known to take a nodule to confirm the presence of a nodule, evaluate for additional nodules and cervical lymph nodes and assess for suspicious sonographic features. The next pace in the evaluation of a thyroid nodule, if they run into the criteria as discussed later, is a fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy [12].

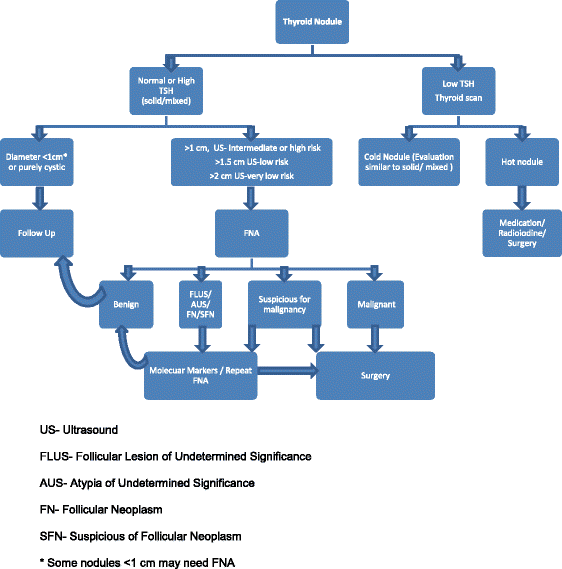

*Algorithm of thyroid nodule work up is presented at the end of the review (Fig. 1).

Thyroid Nodule Workup Algorithm

History and physical examination

Comprehensive history with focus on take a chance factors predicting malignancy (Tabular array ane [1, 3, xiii]) should exist function of the initial evaluation of a patient with thyroid nodule. Symptoms of hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism should be assessed. Patients should be questioned about local pressure symptoms such as difficulty in swallowing or breathing, cough and change in voice.

Physical examination focusing on the thyroid gland assessing the volume and consistency and the nodular features such equally size, number, location and consistency should be performed. Thyroid nodules that are smaller, usually < 1 cm and those located posteriorly or substernally will be difficult to palpate [14, xv]. Cervical lymph nodes should be assessed. Examination of signs of hypo or hyperthyroidism should be done.

Laboratory tests

Serum TSH

Serum TSH should be measured in all patients with thyroid nodules. In patients with low TSH levels, radionuclide thyroid scan should be performed side by side to assess the functional status of the nodule. In a patient with a thyroid nodule, an increased serum TSH or TSH even in the upper limit of normal is associated with increased hazard and an avant-garde phase of malignancy [16, 17].

Serum calcitonin

In patients with thyroid nodules, the routine assessment of serum calcitonin is controversial and there are no definite recommendations for or against it [1, 18, 19]. Many prospective, non-randomized studies, generally from outside United states of america have assessed the value of measuring serum calcitonin [xx–22]. The studies which show that use of serum calcitonin for screening may detect C-cell hyperplasia and MTC at an before stage and overall survival may exist improved, are based on pentagastrin stimulation testing to increment specificity. Pentagastrin is non bachelor in the United States, and in that location is even so an ambiguity almost the sensitivity/specificity, threshold cut off values and cost-effectiveness [22–24]. Imitation-positive calcitonin results may be obtained in patients with hypercalcemia, hypergastrinemia, neuroendocrine tumors, renal insufficiency, papillary and follicular thyroid carcinomas, goiter, chronic autoimmune thyroiditis and prolonged use of certain medications [12, 25, 26]. False negative test upshot may be seen in rare MTCs that do not secrete calcitonin [27, 28].

Serum thyroglobulin (Tg)

In patients with thyroid nodules, routine measurement of serum thyroglobulin is not recommended as it can exist elevated in many thyroid diseases and is neither specific nor sensitive for thyroid cancer [29, 30].

Serum TPO antibodies

Routine measurement of serum anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies is not necessary for thyroid nodule evaluation [31].

Imaging studies

Radionuclide thyroid scan/scintigraphy

In patients with thyroid nodule and a depression serum TSH, suggesting overt or subclinical hyperthyroidism, the next step is to determine if the nodule is apart functioning. Thyroid scintigraphy is useful to determine the functional condition of a nodule.

Scintigraphy, a diagnostic test used in nuclear medicine, utilizing iodine radioisotopes (more than normally used; normally 123I) or technetium pertechnetate (99Tc), measures timed radioisotope uptake by the thyroid gland. The uptake of the radioisotopes will exist greater in hyperfunctioning nodule and will be lower in most benign and virtually all malignant thyroid nodules than side by side normal thyroid tissue [32–34].

Nodules may appear 'hot', 'warm' or 'cold' depending on whether the tracer uptake is greater than, equal to or less than the surrounding normal thyroid tissue respectively [11]. Autonomous nodules may announced hot or indeterminate and business relationship for 5 to 10 % of palpable nodules. FNA evaluation of a hyperfunctioning nodule is non necessary as most hyperfunctioning nodules are benign [i].

Thyroid sonography/ultrasound

Thyroid Ultrasound (U.s.) is a noninvasive imaging technique that should be performed on all patients with nodules suspected clinically or incidentally noted on other imaging studies such as carotid ultrasound, CT, MRI, or 18-FDG-PET scan.

Ultrasound will help confirm the thyroid nodule/due south, assess the size, location and evaluate the composition, echogenicity, margins, presence of calcification, shape and vascularity of the nodules and the adjacent structures in the neck including the lymph nodes. If there are multiple nodules, all the nodules should be assessed for suspicious US characteristics.

FNA conclusion making is guided by both nodule size and ultrasound characteristics, the latter being more predictive of malignancy than size [35, 36]. The nodular characteristics that are associated with a higher likelihood of malignancy include a shape that is taller than broad measured in the transverse dimension, hypoechogenicity, irregular margins, microcalcifications, and absent halo [35–41]. The feature with the highest diagnostic odds ratio for malignancy was suggested to be the nodule being taller than wider [42]. The more suspicious characteristics that the nodule has, it increases the likelihood of malignancy. In contrast, beneficial nodule predicting The states characteristics include purely cystic nodule (< two % risk of malignancy) [39], spongiform appearance (99.7 % specific for benign thyroid nodule) [40, 42–44].

The contempo ATA guidelines classify nodules into 5 risk groups based on United states of america results [ane]. However, the current AACE guidelines suggest a more practical, 3-tier hazard classification: depression hazard, intermediate chance and loftier take chances thyroid lesions, based on their US characteristics [xiii].

In patients with thyroid nodules and depression TSH who have undergone thyroid scintigraphy, ultrasound is useful to check for cyclopedia of the nodule and hyperfunctioning area on the browse, which do not need FNA and to evaluate other nonfunctional or intermediate nodules, which may crave FNA based on sonographic criteria [1].

Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNA)

FNA is considered the aureate standard test for evaluating thyroid nodules. It is an office process, washed under no or local anesthesia with 23 to 27 judge needle, to obtain tissue samples for cytological examination. It is a condom, accurate and cost-effective way for evaluating thyroid nodules [45–54].

FNA can be done using palpation or with ultrasound guidance. The states machines (7.five to 10 MHz transducers), provide clear and continuous visualization of thyroid gland and let for real fourth dimension visualization of the needle tip to ensure accurate sampling. Ultrasound guided technique has lower nondiagnostic and false negative cytology rates compared to palpation technique [48, 55]. US guided FNA is preferred for difficult to palpate nodules, predominantly cystic or posteriorly located nodules [i]. In practise more clinicians are using ultrasound guided FNA (either free hand technique or with the help of a needle guide) over palpation guided technique for all thyroid FNA.

Indications for FNA

Over the years there has been a change in guidelines with regards to judiciously selecting the thyroid nodules for further evaluation with FNA. The approach has been toward a bourgeois direction. The changes are reflected in the recently published ATA guidelines [one] (Table ii).

FNA should not be performed on thyroid nodules < 1 cm in diameter with some exceptions discussed later in this department. For nodules > ane cm, FNA is recommended to further evaluate the thyroid nodule with some exceptions [one].

FNA biopsy is recommended for nodules > i cm with high suspicion features (solid hypoechoic nodule or solid hypoechoic component of a partially cystic nodule with either one or more of features: irregular margin or microcalcification or taller than wide shape or rim calcification or evidence of actress thyroidal extension; estimated malignancy risk of 70–90 %) or > ane cm with intermediate suspicion features (hypoechoic solid nodule with smooth margins without microcalcification, extra thyroidal extension or taller than wide shape; estimated malignancy run a risk 10–xx %). Low suspicion features include isoechoic or hyperechoic solid nodule or partially cystic nodules with eccentric solid areas without the features of highly suspicious nodule (estimated malignancy run a risk of 5–10 %). Cyst drainage may also be performed, especially in symptomatic patients. Very low suspicion features include spongiform (assemblage of multiple microcystic components in more than 50 % of the nodule volume [40, 52]) or partially cystic nodules without the features of the in a higher place mentioned suspicious category features (estimated malignancy risk of < 3 %).

Cervical lymph node assessment (anterior, key and lateral compartment) should exist performed in all patients with thyroid nodule. Suspicious lymph nodes (microcalcification, cystic, peripheral vascularity, hyperechogenicity, round shape [56]) should accept FNA evaluation for cytology and washout Tg measurement. This is one of the scenarios where a subcentimeter thyroid nodule associated with these abnormal cervical lymph nodes should undergo FNA. Likewise in patients with the clinical take chances factors mentioned in Tabular array i and with the high pretest likelihood for thyroid cancer associated with these features, FNA at sizes lower than those recommended can be considered [1, 13]. PET positive nodules have a higher incidence of malignancy ~xl–45 % and FNA is recommended in nodules > 1 cm [1, 57, 58].

The The states features of each nodule should exist assessed independently to determine the demand for FNA biopsy. The nodules that are not biopsied should be monitored with periodic US with follow upwards duration and frequency based on factors including sonographic features and risk factors. Too conservative approach of active surveillance without FNA may be reasonable approach for patients who encounter the above FNA criteria just are at high surgical risk and those with relatively short life expectancy [one].

Cytological diagnosis

FNA cytology of the thyroid nodule is reported using diverse nomenclature systems. In Usa, the Bethesda Arrangement for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology is the most commonly used. The diagnostic groups suggested are [59, 60]:

-

➢ Benign – This includes macrofollicular or adenomatoid/hyperplastic nodules, colloid adenomas (well-nigh common), nodular goiter, lymphocytic and granulomatous thyroiditis. 0–3 % predicted risk of malignancy.

-

➢ Follicular lesion or atypia of undetermined significance (FLUS or AUS) – This includes lesions with singular cells, or mixed macro- and microfollicular nodules. 5–fifteen % predicted chance of malignancy.

-

➢ Follicular neoplasm or suspicious for a follicular tumour (FN/SFN) – This includes microfollicular nodules, including Hurthle cell lesions/ suspicious for Hurthle jail cell neoplasm. fifteen–30 % predicted hazard of malignancy.

-

➢ Suspicious for malignancy. threescore–75 % predicted risk of malignancy.

-

➢ Malignant. This includes PTC (nigh common), MTC, anaplastic carcinoma, and loftier-grade metastatic cancers. 97–99 % predicted risk for malignancy.

-

➢ Nondiagnostic or Unsatisfactory. 1–4 % predicted risk of malignancy.

Other classification systems such as UK-RCPath (Royal Higher of Pathology) or Italian AME Consensus and modifications of these systems are also used to report cytology results [thirteen]. The estimation of the FNA smears is influenced by the expertise of the cytopathologist and in that location is inherent limitation to the reproducibility of the cytopathological results [45, 46, 61, 62]. Accuracy of the results is also influenced by the skill of the operator, FNA technique and specimen preparation. FNA results are categorized as either diagnostic/satisfactory, if it contains at least six groups, each containing of at least 10 well-preserved thyroid epithelial cells, else nondiagnostic/unsatisfactory [11, thirteen]. FNA results are crucial in guiding the further steps in the management of thyroid nodule.

Benign cytology (~seventy % of all FNAs) is the nigh common finding on FNA [13, 45, 48]. Indeterminate results (~ten–15 % of all FNAs), which are without a distinct cytological diagnosis [45, 46, 63], include the diagnostic groups of FLUS/AUS and FN/SFN. This diagnostic group possesses a claiming in terms of adjacent steps for management. In practise, although the bulk of these patients undergo surgery, the majority of the nodules are found benign. Molecular tests have been developed in an attempt to determine whether an indeterminate nodule is benign or malignant.

Nondiagnostic or unsatisfactory smears (~15 % of all FNAs) have inadequate number of cells to make a diagnosis and event from cystic fluid without cells, bloody smears, or improper techniques in preparing slides [11, 64–67].

Molecular markers

The use of molecular markers in thyroid nodules has been suggested for diagnostic purpose in case of indeterminate cytological diagnosis, to assist with decision making most management choice (surgical handling). These tests are performed using samples from needle washings collected during fine needle aspiration biopsy. The molecular tests which take the most available data are: Afirma Gene-expression Classifier [68], 7-cistron panel of genetic mutations and rearrangements [69] and galectin-3 immunohistochemistry [70].

The Afirma gene-expression classifier (167 GEC; mRNA expression of 167 genes) evaluates for the presence of benign cistron expression profile. It has a loftier sensitivity (92 %) and negative predictive (93 %) value but low positive predictive value and specificity (48–53 %) [68, 71]. It is used every bit a rule out examination to identify beneficial nodules. A benign GEC result predicts low risk of malignancy but the nodules classified every bit benign still accept ~5 % hazard of malignancy [71, 72].

The seven factor mutation and rearrangement analysis panel evaluates for BRAF, NRAS, HRAS and KRAS point mutations and common rearrangements of RET/PTC and PAX8/PPARγ. Information technology has a high specificity (86–100 %) and positive predictive value (84–100 %) but poor sensitivity (reported from 44 to 100 %) [69, 73–75]. Information technology is being used as a rule in test for thyroid malignancy.

This field is evolving and many other molecular tests are being adult (mRNA markers, miRNA markers, etc.) [70, 76–80]. None of the bachelor tests can decisively ostend the presence or absence of malignancy in all indeterminate thyroid nodules. Long term data are needed to confirm its utility in clinical practice. Most of the assays are trained on classic papillary cancers and have limited data in follicular cancers. I has to consider functioning of a diagnostic test based on prevalence of the affliction (cancer); at loftier cancer prevalence rate, NPV falls dramatically. Tests are expensive and in deciding their use in direction of indeterminate nodules, one should as well consider the pretest probability of malignancy with clinical risk features, sonographic characteristics and the size of the nodule, the caste of patient concern and patient preferences, and if the patient would be able to come back for a follow up. In the electric current settings, molecular testing should just be used to supplement cytopathologic evaluation or clinical and imaging cess [81]. Patients should be counselled regarding the electric current clinical utility and limitations of these tests. The AACE Guidelines recommend neither for nor against their use in clinical practice [xiii]. This field is new and evolving, the recommendations of the use of these molecular tests tin can be expected to modify in the hereafter.

Management

Various factors including serum TSH, clinical risk gene assessment, size of the nodule, ultrasound characteristics, patient preferences and results of the FNA biopsy should be considered in management of thyroid nodule. FNA biopsy cytological diagnosis is the most crucial determinant in decision making.

For autonomous or hyperfunctioning nodules, if the patient has hyperthyroidism, management options include radioiodine therapy or surgery. If the patient has subclinical hyperthyroidism (low TSH with normal FT4), management depends on clinical risk of complications (atrial fibrillation in patients over the age of 60 to 65 years and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women) and the degree of TSH suppression [82–84].

Nodules less than 1 cm with some exceptions should not be biopsied and followed up closely [i]. Also for these patients the frequency and elapsing of follow up will depend on the boosted risk factors nowadays.

For nodules selected for FNA, direction primarily depends on cytologic results. According to the Bethesda Classification scheme, FNA of the nodules yields half-dozen major results with subsequent unlike direction for each category. However the management of indeterminate nodules (FLUS/AUS and FN/SFN) has similar principles and will exist discussed together.

Nodules with beneficial cytology

The adventure of malignancy in nodules reported as beneficial is 0–3 % [85–88]. Patients with benign nodules are usually managed conservatively without surgery; immediate further diagnostic studies are not required [1]. Though at that place is a run a risk of faux negative results associated with cytology reporting, initial benign FNA has negligible mortality take chances in long term follow up [89].

The frequency and duration of follow up of the benign nodules have been variable in clinical practice. In the nodules that have suddenly enlarged, hemorrhage and cystic degeneration is the most common cause; malignancy is rare even in nodules that have grown [xc, 91]. There is no clear prove to suggest that nodules with larger size (> iii or 4 cm) with benign cytology should be managed differently than smaller nodules [62, 92]. The follow upwards of the benign cytological diagnosis should be decided on the sonographic characteristic of the nodule rather than growth [93, 94].

Per the 2015 ATA guidelines, nodules with high suspicious US pattern should have repeat US and FNA within 12 months; while those with low to intermediate suspicious U.s.a. pattern should have repeat US in 12–24 months. The conclusion to repeat FNA or observe with echo United states of america is based on > xx % growth in at least 2 nodule dimensions or > l % increment in nodule volume or the appearance of new suspicious Us pattern. Nodules with very depression suspicious patterns should have U.s.a. repeated at 24 months or more. Continued surveillance for a nodule with echo 2d benign cytology is not needed [1, 95].

Surgical removal may be needed for benign nodules if they are causing force per unit area or structural symptoms. TSH suppressive therapy has no role in the management of benign nodule. Percutaneous ethanol ablation can be considered for thyroid cysts and certain complex thyroid nodules [13].

Indeterminate nodules (FLUS/ AUS or FN/SFN)

FLUS/AUS and FN/SFN have 5–15 % and fifteen–30 % predicted hazard of malignancy, respectively. Practice pattern vary considerably in management of indeterminate nodules [96]. Molecular tests have impacted the management strategies in this category. The clinical risk factors, US characteristics (Elastography in add-on can be considered in these cases), patient preference and availability/feasibility of the molecular tests should be considered in the decision making process. Some scores such every bit Mcgill thyroid nodule scores have been tried in pre-operative conclusion making in thyroid nodules [97].

FLUS/AUS category includes lesions with focal architecture or nuclear atypia whose significance cannot be further determined and specimens that are limited because of poor fixation or obscuring blood [98]. The interpretation of the features which incorporate this category is based entirely on the observer which results in poor reproducibility and a 2nd review by experienced high volume cytopathologist can be considered [99, 100]. Repeat FNA or molecular testing (actress sample can be nerveless at the time of initial testing) can be considered to supplement the malignancy gamble assessment [68, 69, 101, 102]. If either of them is non performed or inconclusive, based on clinical and United states risk factors and patient preference, either surveillance with repeat US or diagnostic surgery can be chosen [1]. With the new developments in molecular testing, the approach to this category may modify in the future.

For FN/SFN, surgical excision for diagnosis had been an established practice. With the molecular testing being available, it tin can be used to supplement the malignancy risk assessment again afterwards considering the clinical and Us risk factors and patient preference [68, 103]. If the molecular testing is non available/performed or inconclusive, diagnostic surgical excision can be considered. Patients with surgical histology specimens showing benign follicular adenoma (absenteeism of capsular or vascular invasion) do not require further treatment. Still, patients whose surgical histology shows follicular thyroid cancer might demand to accept a completion thyroidectomy [i, 13, 69].

Suspicious for malignancy

This category includes specimens strongly suspicious for malignancy, but lacking diagnostic criteria [60]. Diagnostic surgery and histologic examination would be needed in nearly of the cases. For nodules with the cytology reported every bit suspicious for malignancy, after consideration of clinical and United states of america risk factors and patient preference, molecular tests (seven-factor mutation and rearrangement console) can be considered if it would alter the surgical determination making, which is the recommended modality of direction [one, 69, 104].

Every bit more data become bachelor on the molecular tests, the direction of this category may potentially change in the future.

Malignant

This category includes papillary cancer, follicular carcinoma, Hurthle cell (oncocytic) carcinoma, medullary cancer, thyroid lymphoma, anaplastic cancer, and cancer metastatic to the thyroid. Surgery is generally recommended for these patients [one, 13, 105, 106]. Circumstances in which agile surveillance may be considered include low take chances papillary microcarcinoma (< 1 cm), patients with loftier surgical take chances, brusk life expectancy and if concurrent surgical or medical bug need to be addressed get-go. For cancer due to metastasis, further investigations to find the primary lesion should be undertaken.

Nondiagnostic

This category includes cytologically inadequate specimen. If no or scant follicular tissue is obtained, the absence of malignant cells does not mean a negative biopsy in patients with nondiagnostic FNA. In such cases, FNA using The states-guidance should exist repeated and if possible with onsite cytological cess [one, 13, 107]. If the results are still nondiagnostic, cadre needle biopsy or shut observation or diagnostic surgical excision can be considered depending on the suspicious pattern on sonography, clinical risk factors and growth of the nodule during active surveillance [1, 108, 109].

Pregnancy

The evaluation of a thyroid nodule in a pregnant woman should be done in aforementioned style equally one would in nonpregnant state. However, for the pregnant women with nodule and suppressed TSH that persists later first trimester, further evaluation can exist delayed afterwards pregnancy and cessation of lactation when the radionuclide browse can be performed. For a nodule with FNA suggesting PTC, if it is discovered early in pregnancy and if it grows substantially (twenty % growth in at least ii dimensions or 50 % increase in book or new suspicious US pattern) by 24 weeks gestation or if suspicious cervical lymph nodes are noted on US, surgery should be considered during the second trimester of pregnancy. Notwithstanding, if information technology is diagnosed in the latter half of the pregnancy or if it is diagnosed early in the pregnancy and remains stable by midgestation, surgery may be performed after commitment. Consideration could be given to assistants of levothyroxine therapy to continue the TSH in the range of 0.i–one mU/L [1, thirteen, 110–112].

Conclusions

Thyroid nodules are common and carry a iv–six.5 % adventure of malignancy. The initial evaluation in all patients with a thyroid nodule includes a detailed history and physical examination assessing risk factors, measurement of serum TSH and neck ultrasonography to assess the size and suspicious characteristics. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is an accurate and toll constructive way to evaluate thyroid nodules. Nodules with diameter < i cm with some exceptions crave no FNA and can exist observed with a follow up Us. Patients with benign nodules are usually followed without surgery. Where available, mRNA classifier system or mutational analysis can exist used for further evaluating FNA aspirates with cytology of follicular neoplasm or follicular lesion/ atypia of undetermined significance. Patients with cytology suggesting cancer should be referred for surgery. The loftier prevalence and increasing diagnosis of incidental thyroid nodules requires clinicians to prefer testify-based approaches to evaluate, risk stratify and provide appropriate treatment. As more than show becomes available, active surveillance may become possible for selected cases of thyroid cancer patients.

References

-

Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Clan Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Forcefulness on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(ane):1–133.

-

Tunbridge WM, Evered DC, Hall R, et al. The spectrum of thyroid affliction in a customs: the Whickham survey. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1977;7(6):481–93.

-

Hegedus Fifty. Clinical practice. The thyroid nodule. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(17):1764–71.

-

Dean DS, Gharib H. Epidemiology of thyroid nodules. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22(vi):901–xi.

-

Davies Fifty, Welch HG. Current thyroid cancer trends in the Usa. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Cervix Surg. 2014;140(4):317–22.

-

Li Due north, Du XL, Reitzel LR, Xu L, Sturgis EM. Impact of enhanced detection on the increase in thyroid cancer incidence in the The states: review of incidence trends by socioeconomic condition within the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results registry, 1980–2008. Thyroid. 2013;23(one):103–x.

-

Werk Jr EE, Vernon BM, Gonzalez JJ, Ungaro PC, McCoy RC. Cancer in thyroid nodules. A customs hospital survey. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144(3):474–6.

-

Belfiore A, Giuffrida D, La Rosa GL, et al. Loftier frequency of cancer in cold thyroid nodules occurring at young age. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1989;121(ii):197–202.

-

Lin JD, Chao TC, Huang BY, Chen ST, Chang HY, Hsueh C. Thyroid cancer in the thyroid nodules evaluated by ultrasonography and fine-needle aspiration cytology. Thyroid. 2005;15(7):708–17.

-

Tan GH, Gharib H. Thyroid incidentalomas: management approaches to nonpalpable nodules discovered incidentally on thyroid imaging. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(3):226–31.

-

Gharib H, Papini E. Thyroid nodules: clinical importance, cess, and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2007;36(3):707–35. vi.

-

Castro MR, Gharib H. Continuing controversies in the management of thyroid nodules. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(11):926–31.

-

Gharib H, Papini Eastward, Garber JR, et al. American Clan of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Associazione Medici Endocrinologi Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practise for the Diagnosis and Direction of Thyroid Nodules - 2016 Update. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(v):622–39.

-

Tan GH, Gharib H, Reading CC. Solitary thyroid nodule. Comparing betwixt palpation and ultrasonography. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(22):2418–23.

-

Singh S, Singh A, Khanna AK. Thyroid incidentaloma. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2012;3(3):173–81.

-

Boelaert M, Horacek J, Holder RL, Watkinson JC, Sheppard MC, Franklyn JA. Serum thyrotropin concentration equally a novel predictor of malignancy in thyroid nodules investigated by fine-needle aspiration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(eleven):4295–301.

-

Haymart MR, Repplinger DJ, Leverson GE, et al. Higher serum thyroid stimulating hormone level in thyroid nodule patients is associated with greater risks of differentiated thyroid cancer and advanced tumor stage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):809–fourteen.

-

Costante G, Filetti S. Early on diagnosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma: is systematic calcitonin screening appropriate in patients with nodular thyroid disease? Oncologist. 2011;16(ane):49–52.

-

Gharib H, Papini E, Paschke R. Thyroid nodules: a review of current guidelines, practices, and prospects. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159(5):493–505.

-

Elisei R, Bottici V, Luchetti F, et al. Impact of routine measurement of serum calcitonin on the diagnosis and effect of medullary thyroid cancer: experience in 10,864 patients with nodular thyroid disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(1):163–eight.

-

Niccoli P, Wion-Barbot N, Caron P, et al. Interest of routine measurement of serum calcitonin: written report in a large series of thyroidectomized patients. The French Medullary Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(2):338–41.

-

Costante G, Meringolo D, Durante C, et al. Predictive value of serum calcitonin levels for preoperative diagnosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma in a cohort of 5817 sequent patients with thyroid nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(2):450–5.

-

Machens A, Hoffmann F, Sekulla C, Dralle H. Importance of gender-specific calcitonin thresholds in screening for occult desultory medullary thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;xvi(4):1291–8.

-

Chambon G, Alovisetti C, Idoux-Louche C, et al. The use of preoperative routine measurement of basal serum thyrocalcitonin in candidates for thyroidectomy due to nodular thyroid disorders: results from 2733 consecutive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(i):75–81.

-

Toledo SP, Lourenco Jr DM, Santos MA, Tavares MR, Toledo RA, Correia-Deur JE. Hypercalcitoninemia is not pathognomonic of medullary thyroid carcinoma. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(seven):699–706.

-

Erdogan MF, Gursoy A, Kulaksizoglu Grand. Long-term effects of elevated gastrin levels on calcitonin secretion. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006;29(9):771–v.

-

Wang TS, Ocal It, Sosa JA, Cox H, Roman S. Medullary thyroid carcinoma without marked elevation of calcitonin: a diagnostic and surveillance dilemma. Thyroid. 2008;18(8):889–94.

-

Dora JM, Canalli MH, Capp C, Punales MK, Vieira JG, Maia AL. Normal perioperative serum calcitonin levels in patients with advanced medullary thyroid carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Thyroid. 2008;eighteen(8):895–nine.

-

Suh I, Vriens MR, Guerrero MA, et al. Serum thyroglobulin is a poor diagnostic biomarker of malignancy in follicular and Hurthle-cell neoplasms of the thyroid. Am J Surg. 2010;200(1):41–6.

-

Lee EK, Chung KW, Min HS, et al. Preoperative serum thyroglobulin equally a useful predictive marking to differentiate follicular thyroid cancer from beneficial nodules in indeterminate nodules. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27(9):1014–eight.

-

Repplinger D, Bargren A, Zhang YW, Adler JT, Haymart 1000, Chen H. Is Hashimoto's thyroiditis a chance factor for papillary thyroid cancer? J Surg Res. 2008;150(i):49–52.

-

Shambaugh third GE, Quinn JL, Oyasu R, Freinkel N. Disparate thyroid imaging. Combined studies with sodium pertechnetate Tc 99 m and radioactive iodine. Jama. 1974;228(7):866–9.

-

Blum Yard, Goldman AB. Improved diagnosis of "nondelineated" thyroid nodules by oblique scintillation scanning and echography. J Nucl Med. 1975;16(8):713–5.

-

Reschini E, Ferrari C, Castellani M, et al. The trapping-simply nodules of the thyroid gland: prevalence study. Thyroid. 2006;16(8):757–62.

-

Leenhardt L, Hejblum Thou, Franc B, et al. Indications and limits of ultrasound-guided cytology in the management of nonpalpable thyroid nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(1):24–8.

-

Papini East, Guglielmi R, Bianchini A, et al. Risk of malignancy in nonpalpable thyroid nodules: predictive value of ultrasound and colour-Doppler features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(5):1941–vi.

-

Nam-Goong IS, Kim HY, Gong G, et al. Ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration of thyroid incidentaloma: correlation with pathological findings. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;lx(one):21–8.

-

Cappelli C, Castellano M, Pirola I, et al. The predictive value of ultrasound findings in the direction of thyroid nodules. QJM. 2007;100(1):29–35.

-

Frates MC, Benson CB, Doubilet PM, et al. Prevalence and distribution of carcinoma in patients with solitary and multiple thyroid nodules on sonography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(9):3411–7.

-

Moon WJ, Jung SL, Lee JH, et al. Benign and malignant thyroid nodules: United states differentiation--multicenter retrospective study. Radiology. 2008;247(three):762–seventy.

-

Remonti LR, Kramer CK, Leitao CB, Pinto LC, Gross JL. Thyroid ultrasound features and adventure of carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-assay of observational studies. Thyroid. 2015;25(five):538–50.

-

Brito JP, Gionfriddo MR, Al Nofal A, et al. The accuracy of thyroid nodule ultrasound to predict thyroid cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(4):1253–63.

-

Bonavita JA, Mayo J, Babb J, et al. Design recognition of beneficial nodules at ultrasound of the thyroid: which nodules can be left solitary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(1):207–13.

-

Moon WJ, Kwag HJ, Na DG. Are at that place any specific ultrasound findings of nodular hyperplasia ("go out me alone" lesion) to differentiate it from follicular adenoma? Acta Radiol. 2009;50(4):383–8.

-

Gharib H. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules: advantages, limitations, and effect. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69(1):44–ix.

-

Gharib H, Goellner JR. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules. Endocr Pract. 1995;one(6):410–seven.

-

Bomeli SR, LeBeau SO, Ferris RL. Evaluation of a thyroid nodule. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2010;43(2):229–38. vii.

-

Castro MR, Gharib H. Thyroid fine-needle aspiration biopsy: progress, practice, and pitfalls. Endocr Pract. 2003;9(ii):128–36.

-

Jeffrey Lead, Miller TR. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of the thyroid. Pathology (Phila). 1996;4(2):319–35.

-

Hamberger B, Gharib H, Melton 3rd LJ, Goellner JR, Zinsmeister AR. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules. Impact on thyroid exercise and toll of care. Am J Med. 1982;73(3):381–iv.

-

Hamburger JI, Hamburger SW. Fine needle biopsy of thyroid nodules: avoiding the pitfalls. Northward Y Country J Med. 1986;86(five):241–9.

-

Sakorafas GH. Thyroid nodules; estimation and importance of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) for the clinician - practical considerations. Surg Oncol. 2010;19(4):e130–9.

-

Can AS. Toll-effectiveness comparison between palpation- and ultrasound-guided thyroid fine-needle aspiration biopsies. BMC Endocr Disord. 2009;9:14.

-

Singh Ospina N, Brito JP, Maraka South, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy for thyroid malignancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2016;53:651–61.

-

Danese D, Sciacchitano S, Farsetti A, Andreoli Thousand, Pontecorvi A. Diagnostic accurateness of conventional versus sonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules. Thyroid. 1998;viii(1):15–21.

-

Leenhardt Fifty, Erdogan MF, Hegedus L, et al. 2013 European thyroid association guidelines for cervical ultrasound browse and ultrasound-guided techniques in the postoperative direction of patients with thyroid cancer. Eur Thyroid J. 2013;2(three):147–59.

-

Yoon JH, Cho A, Lee HS, Kim EK, Moon HJ, Kwak JY. Thyroid incidentalomas detected on xviii F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography: Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TIRADS) in the diagnosis and management of patients. Surgery. 2015;158(5):1314–22.

-

Flukes South, Lenzo N, Moschilla Chiliad, Sader C. Positron emission tomography-positive thyroid nodules: rate of malignancy and histological features. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86(6):487–91.

-

Baloch ZW, LiVolsi VA, Asa SL, et al. Diagnostic terminology and morphologic criteria for cytologic diagnosis of thyroid lesions: a synopsis of the National Cancer Found Thyroid Fine-Needle Aspiration State of the Science Conference. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36(six):425–37.

-

Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The Bethesda Organisation for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid. 2009;nineteen(11):1159–65.

-

Gharib H, Goellner JR. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the thyroid: an appraisal. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(4):282–9.

-

Pinchot SN, Al-Wagih H, Schaefer S, Sippel R, Chen H. Accuracy of fine-needle aspiration biopsy for predicting tumour or carcinoma in thyroid nodules 4 cm or larger. Arch Surg. 2009;144(seven):649–55.

-

Cersosimo E, Gharib H, Suman VJ, Goellner JR. "Suspicious" thyroid cytologic findings: outcome in patients without immediate surgical treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68(four):343–eight.

-

Gharib H, Goellner JR, Zinsmeister AR, Grant CS, Van Heerden JA. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the thyroid. The problem of suspicious cytologic findings. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101(1):25–8.

-

Chow LS, Gharib H, Goellner JR, van Heerden JA. Nondiagnostic thyroid fine-needle aspiration cytology: direction dilemmas. Thyroid. 2001;11(12):1147–51.

-

Schmidt T, Riggs MW, Speights Jr VO. Significance of nondiagnostic fine-needle aspiration of the thyroid. South Med J. 1997;90(12):1183–6.

-

McHenry CR, Walfish PG, Rosen IB. Non-diagnostic fine needle aspiration biopsy: a dilemma in direction of nodular thyroid affliction. Am Surg. 1993;59(7):415–9.

-

Alexander EK, Kennedy GC, Baloch ZW, et al. Preoperative diagnosis of beneficial thyroid nodules with indeterminate cytology. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(8):705–fifteen.

-

Nikiforov YE, Ohori NP, Hodak SP, et al. Impact of mutational testing on the diagnosis and direction of patients with cytologically indeterminate thyroid nodules: a prospective analysis of 1056 FNA samples. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(xi):3390–7.

-

Bartolazzi A, Orlandi F, Saggiorato Due east, et al. Galectin-3-expression analysis in the surgical selection of follicular thyroid nodules with indeterminate fine-needle aspiration cytology: a prospective multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(vi):543–9.

-

Alexander EK, Schorr G, Klopper J, et al. Multicenter clinical experience with the Afirma gene expression classifier. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(1):119–25.

-

Marti JL, Avadhani V, Donatelli LA, et al. Wide Inter-institutional Variation in Performance of a Molecular Classifier for Indeterminate Thyroid Nodules. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(12):3996–4001.

-

Cantara S, Capezzone Thousand, Marchisotta Due south, et al. Affect of proto-oncogene mutation detection in cytological specimens from thyroid nodules improves the diagnostic accuracy of cytology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(3):1365–9.

-

Nikiforov YE, Steward DL, Robinson-Smith TM, et al. Molecular testing for mutations in improving the fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of thyroid nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(6):2092–eight.

-

Beaudenon-Huibregtse S, Alexander EK, Guttler RB, et al. Centralized molecular testing for oncogenic factor mutations complements the local cytopathologic diagnosis of thyroid nodules. Thyroid. 2014;24(10):1479–87.

-

Franco C, Martinez V, Allamand JP, et al. Molecular markers in thyroid fine-needle aspiration biopsy: a prospective study. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2009;17(3):211–v.

-

Fadda G, Rossi ED, Raffaelli Chiliad, et al. Follicular thyroid neoplasms can be classified as low- and high-adventure according to HBME-1 and Galectin-3 expression on liquid-based fine-needle cytology. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165(3):447–53.

-

Prasad NB, Somervell H, Tufano RP, et al. Identification of genes differentially expressed in beneficial versus cancerous thyroid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;fourteen(11):3327–37.

-

Nikiforova MN, Tseng GC, Steward D, Diorio D, Nikiforov YE. MicroRNA expression profiling of thyroid tumors: biological significance and diagnostic utility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(five):1600–viii.

-

Agretti P, Ferrarini E, Rago T, et al. MicroRNA expression profile helps to distinguish beneficial nodules from papillary thyroid carcinomas starting from cells of fine-needle aspiration. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167(three):393–400.

-

Bernet V, Hupart KH, Parangi S, Woeber KA. AACE/ACE affliction state commentary: molecular diagnostic testing of thyroid nodules with indeterminate cytopathology. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(four):360–three.

-

Bauer DC, Rodondi N, Stone KL, Hillier TA. Thyroid hormone apply, hyperthyroidism and mortality in older women. Am J Med. 2007;120(4):343–ix.

-

Auer J, Scheibner P, Mische T, Langsteger W, Eber O, Eber B. Subclinical hyperthyroidism as a hazard factor for atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2001;142(5):838–42.

-

Biondi B, Cooper DS. The clinical significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Endocr Rev. 2008;29(1):76–131.

-

Orlandi A, Puscar A, Capriata E, Fideleff H. Repeated fine-needle aspiration of the thyroid in benign nodular thyroid affliction: critical evaluation of long-term follow-up. Thyroid. 2005;15(iii):274–8.

-

Illouz F, Rodien P, Saint-Andre JP, et al. Usefulness of repeated fine-needle cytology in the follow-up of non-operated thyroid nodules. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156(3):303–eight.

-

Oertel YC, Miyahara-Felipe L, Mendoza MG, Yu Yard. Value of repeated fine needle aspirations of the thyroid: an analysis of over ten thousand FNAs. Thyroid. 2007;17(11):1061–6.

-

Tee YY, Lowe AJ, Brand CA, Judson RT. Fine-needle aspiration may miss a third of all malignancy in palpable thyroid nodules: a comprehensive literature review. Ann Surg. 2007;246(5):714–20.

-

Nou E, Kwong N, Alexander LK, Cibas ES, Marqusee East, Alexander EK. Determination of the optimal time interval for repeat evaluation after a benign thyroid nodule aspiration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):510–half dozen.

-

Kim SY, Han KH, Moon HJ, Kwak JY, Chung WY, Kim EK. Thyroid nodules with benign findings at cytologic test: results of long-term follow-upwards with US. Radiology. 2014;271(1):272–81.

-

Ashcraft MW, Van Herle AJ. Management of thyroid nodules. II: Scanning techniques, thyroid suppressive therapy, and fine needle aspiration. Head Cervix Surg. 1981;3(four):297–322.

-

Yoon JH, Kwak JY, Moon HJ, Kim MJ, Kim EK. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy and the sonographic differences between beneficial and malignant thyroid nodules 3 cm or larger. Thyroid. 2011;21(9):993–m.

-

Kwak JY, Koo H, Youk JH, et al. Value of US correlation of a thyroid nodule with initially benign cytologic results. Radiology. 2010;254(1):292–300.

-

Rosario PW, Purisch S. Ultrasonographic characteristics every bit a benchmark for echo cytology in benign thyroid nodules. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2010;54(1):52–5.

-

Durante C, Costante Thou, Lucisano Chiliad, et al. The natural history of benign thyroid nodules. Jama. 2015;313(9):926–35.

-

Burch HB, Burman KD, Cooper DS, Hennessey JV, Vietor NO. A 2015 Survey of Clinical Practice Patterns in the Management of Thyroid Nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(seven):2853–62. jc20161155.

-

Varshney R, Wood Six, Mascarella MA, et al. The Mcgill thyroid nodule score - does it assistance with indeterminate thyroid nodules? J Otolaryngol Caput Neck Surg. 2015;44:2.

-

Shi Y, Ding X, Klein M, et al. Thyroid fine-needle aspiration with atypia of undetermined significance: a necessary or optional category? Cancer. 2009;117(5):298–304.

-

Davidov T, Trooskin SZ, Shanker BA, et al. Routine second-stance cytopathology review of thyroid fine needle aspiration biopsies reduces diagnostic thyroidectomy. Surgery. 2010;148(6):1294–ix. give-and-take 9–301.

-

Cibas ES, Baloch ZW, Fellegara Grand, et al. A prospective assessment defining the limitations of thyroid nodule pathologic evaluation. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(5):325–32.

-

Baloch Z, LiVolsi VA, Jain P, et al. Role of repeat fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) in the management of thyroid nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29(4):203–vi.

-

Yang J, Schnadig V, Logrono R, Wasserman PG. Fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules: a study of 4703 patients with histologic and clinical correlations. Cancer. 2007;111(five):306–15.

-

Nikiforov YE, Carty SE, Chiosea SI, et al. Highly accurate diagnosis of cancer in thyroid nodules with follicular neoplasm/suspicious for a follicular neoplasm cytology by ThyroSeq v2 next-generation sequencing analysis. Cancer. 2014;120(23):3627–34.

-

Moon HJ, Kwak JY, Kim EK, et al. The role of BRAFV600E mutation and ultrasonography for the surgical direction of a thyroid nodule suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma on cytology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(eleven):3125–31.

-

Gharib H, Papini E, Paschke R, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, and EuropeanThyroid Association Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the Diagnosis and Direction of Thyroid Nodules. Endocr Pract. 2010;xvi Suppl 1:i–43.

-

Cobin RH, Gharib H, Bergman DA, et al. AACE/AAES medical/surgical guidelines for clinical practice: management of thyroid carcinoma. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. American College of Endocrinology. Endocr Pract. 2001;7(3):202–20.

-

Orija IB, Pineyro M, Biscotti C, Reddy SS, Hamrahian AH. Value of repeating a nondiagnostic thyroid fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Endocr Pract. 2007;13(7):735–42.

-

Suh CH, Baek JH, Kim KW, et al. The Part of Core-Needle Biopsy for Thyroid Nodules with Initially Nondiagnostic Fine-Needle Aspiration Results: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(half dozen):679–88.

-

Moon HJ, Kwak JY, Choi YS, Kim EK. How to manage thyroid nodules with 2 sequent not-diagnostic results on ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration. World J Surg. 2012;36(3):586–92.

-

Moosa Grand, Mazzaferri EL. Event of differentiated thyroid cancer diagnosed in pregnant women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(9):2862–6.

-

Uruno T, Shibuya H, Kitagawa W, Nagahama Yard, Sugino G, Ito K. Optimal timing of surgery for differentiated thyroid cancer in pregnant women. Earth J Surg. 2014;38(3):704–8.

-

Messuti I, Corvisieri S, Bardesono F, et al. Touch on of pregnancy on prognosis of differentiated thyroid cancer: clinical and molecular features. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170(5):659–66.

-

Schneider AB, Ron E, Lubin J, Stovall M, Gierlowski TC. Dose–response relationships for radiation-induced thyroid cancer and thyroid nodules: evidence for the prolonged furnishings of radiations on the thyroid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77(2):362–9.

-

Curtis RE, Rowlings PA, Deeg HJ, et al. Solid cancers after bone marrow transplantation. Northward Engl J Med. 1997;336(xiii):897–904.

-

Pacini F, Vorontsova T, Demidchik EP, et al. Mail-Chernobyl thyroid carcinoma in Belarus children and adolescents: comparison with naturally occurring thyroid carcinoma in Italy and French republic. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(xi):3563–9.

-

Shibata Y, Yamashita S, Masyakin VB, Panasyuk GD, Nagataki S. xv years after Chernobyl: new evidence of thyroid cancer. Lancet. 2001;358(9297):1965–6.

-

Hemminki G, Eng C, Chen B. Familial risks for nonmedullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(10):5747–53.

-

McCartney CR, Stukenborg GJ. Decision analysis of discordant thyroid nodule biopsy guideline criteria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(viii):3037–44.

-

Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al. Revised American Thyroid Association direction guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19(11):1167–214.

-

Moon WJ, Baek JH, Jung SL, et al. Ultrasonography and the ultrasound-based management of thyroid nodules: consensus argument and recommendations. Korean J Radiol. 2011;12(1):1–14.

Acknowledgements

Non applicable.

Funding

No funding sources.

Availability of data and materials

Non applicable.

Authors' contributions

ST was involved in literature search/review and formulation and writing the manuscript. HG provided guidance regarding the literature. HG also assisted with manuscript writing/review. All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/cypher/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Near this article

Cite this article

Tamhane, Southward., Gharib, H. Thyroid nodule update on diagnosis and management. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol two, 17 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40842-016-0035-seven

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40842-016-0035-7

Keywords

- Thyroid

- Thyroid nodules

- Molecular markers

- Beneficial

- Malignant

- FNA

- Management

- Ultrasonography

What Size Thyroid Nodule Should Be Removed,

Source: https://clindiabetesendo.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40842-016-0035-7

Posted by: bateshipleoped.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Size Thyroid Nodule Should Be Removed"

Post a Comment